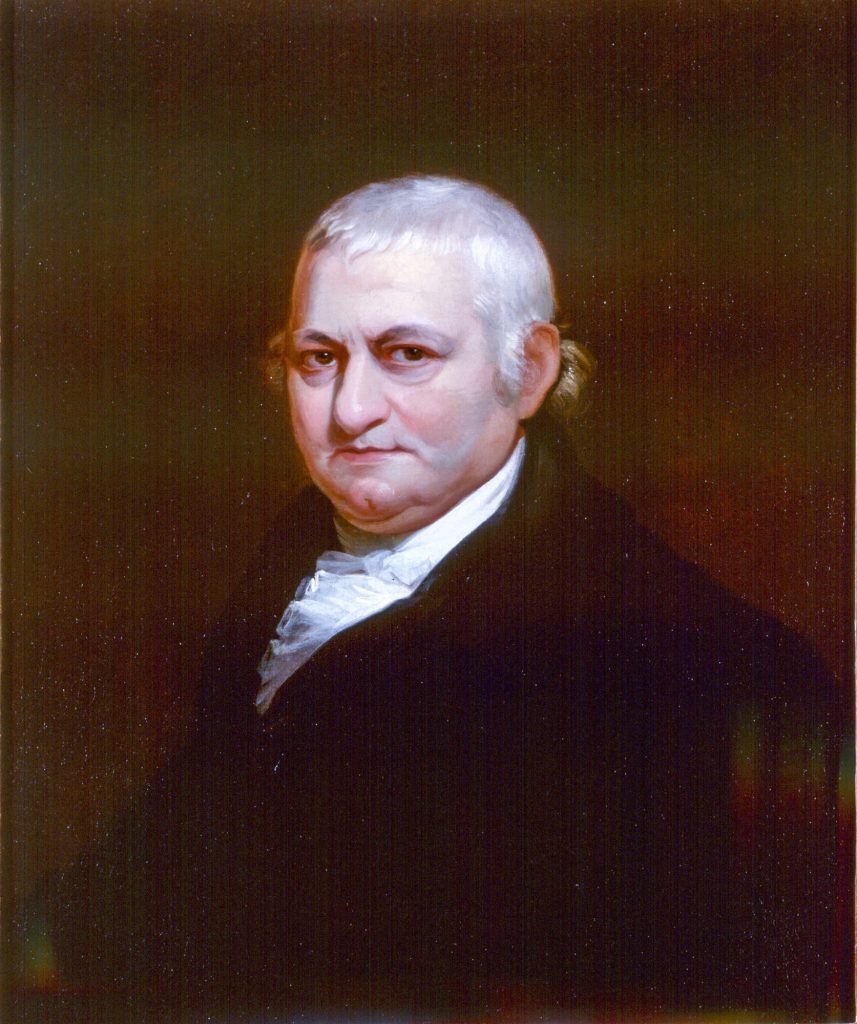

Little is known about the life of Aaron Levy prior to his arrival in Pennsylvania. Family tradition has it that he was born in 1742, and arrived in North America in 1760, at age eighteen. Surviving documents reveal that his family was of Ashkenazi background and deeply religious. As his brother Moses resided in Amsterdam throughout his life, it is likely that Levy himself was raised there.

It did not take Levy long after his arrival to determine that the future development of Pennsylvania lay to the West. Accordingly, Levy soon joined the bevy of land speculators, both Jewish and Christian, who migrated between Philadelphia and Lancaster, buying up whatever tracts they could with the hope of developing them or selling individual parcels to settlers at a profit. The earliest surviving deed in which Levy appears is for a lot in Sunbury in Northumberland County, which he purchased in just three months after the county was established in 1772. Most of the tracts he subsequently purchased also lay in Northumberland County, which encompassed the new territory ceded Pennsylvania under the terms of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, and thus comprised nearly a third of the territory then part of the colony. By 1774, Levy had set up his household in the new township of Northumberland, near Sunbury, where tax lists and other documents describe him as a “merchant.” By 1775 he was joined by his wife, Rachel, and a nephew.

A story told in a family letter of the mid-nineteenth century indicates that Levy met his wife, Rachel Phillips, while she was working as a servant. Walking one Saturday in Philadelphia, he came upon a young woman scrubbing the steps of a house on Third Street and weeping. When he asked her what was wrong, she reported that she was Jewish and that her master was making her work even though it was the Sabbath. Levy was moved, and immediately redeemed her indenture. Then he married her. The date of their marriage is unknown, and they remained childless.

The Revolutionary War brought significant changes to Levy’s business activities. The value of his land holdings declined abruptly when Indians, encouraged by British agents, attacked settlements on the Pennsylvania frontier. A 1778 massacre in the township of Wyoming led to wholesale panic in the vicinity, and a mass exodus of settlers from the Northumberland frontier toward the more populous portion of the colony to the east. Like their neighbors, the Levys removed to the safety of Lancaster and remained there for the duration of the war. In Lancaster, Levy was already well acquainted with the circle of Joseph Simon, and soon became an associate of Michael and Barnard Gratz as well. It was also through Simon that Levy became acquainted with financial strategist Robert Morris and the jurist and statesman James Wilson, both of whom were already involved with Simon and the Gratzes in land purchasing companies. Levy soon became another of their partners in such transactions. Morris, in particular, engaged Levy in loaning money to the Continental Congress, for the purpose of furthering the war against Britain – a debt that was never fully repaid.

After the successful conclusion of the war in 1783, Levy resumed his speculations in western lands, spurred in part by the renewed influx of new settlers and the consequent rise in the value of his holdings. He applied for as many new grants as he could obtain. Levy’s most ambitious scheme involved the purchase of a 335-acre tract west of Northumberland township, where he aimed to create “an inland city” on the route between Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) and Philadelphia that he hoped to turn into a new capitol for the state. In May 1786, Levy issued a broadside proclaiming the proposed creation of the town, highlighting its many conveniences and offering to sell the town lots by lottery. Within 6 months, Levy had registered a town plan for “Aaronsburgh” with provisions for streets, public squares and house lots, with the recorder’s office for Northumberland County. Sale of the town lots had proceeded by November that year, with both Jews and Christians among the purchasers. However, a subsequent economic crisis slowed emigration to the United States to a trickle, and the town never developed as Levy had envisioned. Jewish settlers either stayed in Lancaster or migrated elsewhere, leaving theirs the only Jewish household in the vicinity, and in addition Levy’s business transactions often took him to Philadelphia, which made for a tedious journey. Seeking to ease the burden of constant travel as well as a sense of Jewish community, the Levy’s moved back to Philadelphia in 1794.

Without children of their own, Aaron and Rachel developed a fond affection for the children of Michael and Miriam Gratz, just down the street, to whom they gave preference over their own blood relations. Levy was especially close to the eldest, Simon, whom he and his wife treated as an adopted son. Levy not only sponsored Simon’s entry into trade, but also served as a mentor when it came to land speculating. In 1805, Gratz would follow in Levy’s footsteps to create a town to which he gave his name—the borough of Gratz, located near Harrisburg, in Dauphin County. By that time, Levy had already designated Simon the principal beneficiary of his will, leaving to him the bulk of his substantial landholdings along with the sentimental bequest of a pair of miniatures depicting himself and Rachel. Rachel died in Philadelphia in December of 1810, and Aaron survived her by just four years. They were buried together in Congregation Mikve Israel’s cemetery on Spruce Street.