In his 1890 obituary in the New York Times, August Belmont’s life was described as that of a “leader in finance, politics, society and on the turf.”

Belmont was born Aaron Schönberg, son of Frederika Elsass Simon Schönberg, in the city of Alzay, in Hesse in 1813. Shortly after his mother’s death, at the age of seven, he moved to Frankfurt am Main under the care of his uncle and grandmother. There August studied at the Philanthropin, the liberal Jewish school and gymnasium. He left school in 1828, without having completed a degree, and took a job as an apprentice with the Rothschild’s firm in Frankfurt. By 1832 he had been promoted to clerk, traveling throughout Europe on Rothschild business.

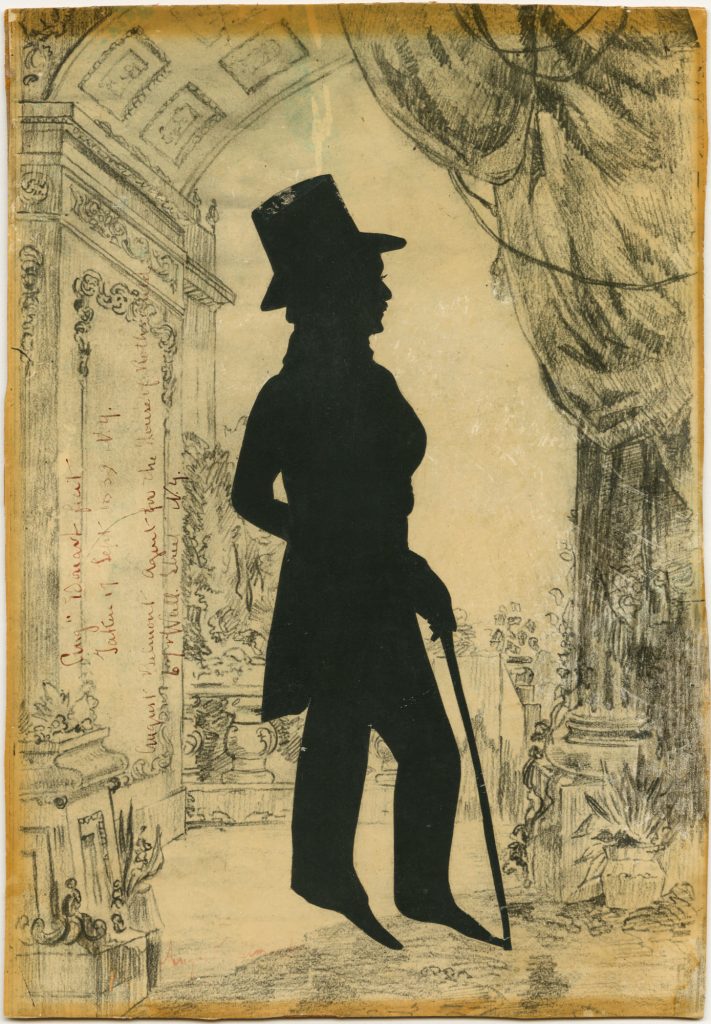

In 1837 Belmont set sail for Havana to oversee the Rothschild firm’s interests there. He never made it to Cuba. Disembarking for a stopover in New York, Belmont encountered the United States in the grips of economic upheaval: the Panic of 1837. Hundreds of American businesses had collapsed, including the Rothschild’s own agent in New York. So, Belmont set up his own firm, August Belmont & Company, swiftly restoring to health the Rothschild’s American interests—loans, foreign exchange and corporate, railroad, and real estate transactions.

In 1844 he was appointed consul-general of the Austrian Empire in New York? Though he resigned the post six years later, it may have whetted his appetite for politics.

In 1849 he married Caroline Slidell Perry, daughter of U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry. Their wedding was a major event in New York society. Belmont purchased a mansion in North Babylon on Long Island, NY—now Belmont Lake State Park. August and Caroline had six children, including four sons, each of whom enjoyed distinguished political careers.

Caroline’s uncle, John Slidell, a Louisiana senator, took Belmont under his wing. August’s first foray into politics came as the campaign manager for James Buchanan’s unsuccessful 1852 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. In 1853 Belmont President Franklin Pierce appointed Belmont United States ambassador to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, a position he retained until 1857.

Because of his vocal support for the idea then popular among many Democratic and Southern politicians that the United States should acquire Cuba as a new slave state, Belmont was denied an ambassadorship to Spain by President James Buchanan. Returning home, he served as a delegate to the 1860 Democratic National Convention, where he supported Stephen A. Douglas, who in turn named Belmont chair of the Democratic National Committee. With the outbreak of the Civil War a few months later, however, Belmont became a staunch supporter of the Union, a so-called “War Democrat.” He actively entreated European banks and heads of state not to lend money or offer aid the Confederacy.

Belmont continued to serve as chairman of the Democratic National Committee until 1872, transforming the position from a largely symbolic post to one of influence. He played a pivotal role in reshaping the Democratic Party after the Civil War. Even after he stepped down, he continued to wield influence in Democratic politics and national political discourse.

During his lifetime, Belmont was known for throwing lavish balls and for his interest in horseracing. President of the National Jockey Club in 1866 and 1867, he bred horses and financed the Triple Crown thoroughbred race the bears his name—the Belmont Stakes.

In The Age of Innocence, novelist Edith Wharton based her character Julius Beaufort on Belmont. “The question was,” Wharton wrote, “who was Beaufort? He passed for an Englishman, was agreeable, handsome, ill-tempered, hospitable and witty. He had come to America with letters of recommendation from old Mrs. Manson Mingott’s English son-in-law, the banker, and had speedily made himself an important position in the world of affairs; but his habits were dissipated, his tongue was bitter, his antecedents were mysterious.”